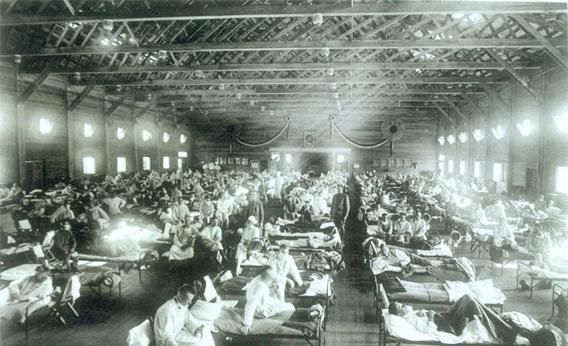

A ward at Camp Funston, Kan. showing the many ill patients who caught the 1918 Spanish influenza

A ward at Camp Funston, Kan. showing the many ill patients who caught the 1918 Spanish influenzaPhotograph by an unkown U.S. Army photographer.

Ninety-five years ago in the little town of Brevig Mission, Alaska, a deadly new virus called Spanish influenza struck quickly and brutally. It killed 90 percent of the town?s Inuit population, leaving scores of corpses that few survivors were willing to touch. The Alaskan territorial government hired gold miners from Nome to travel to flu-ravaged towns and bury the dead. The miners arrived in Brevig Mission shortly after the medical calamity, tossed the victims into a pit two meters deep, and covered them with permafrost.

The flu victims remained untouched until 1951, when a team of scientists dug up the bodies, cracked open four cadavers? rib cages, scooped out chunks of their lungs, and studied the tissue in a lab. But they were unable to recover the virus and threw out the specimens. Nearly 50 years later, scientists dug up another victim from the same site, this time a better preserved, mostly frozen, obese woman, and successfully extracted viral RNA. In 2005, a team of scientists finally completed the project, sequencing the full genome of the viral RNA. But they still don?t know exactly why it caused the Spanish flu pandemic. ??

There?s no single reason why the deadliest pandemic in modern history is still mysterious. Scientists have pinpointed the origins of recent influenza outbreaks like swine flu and bird flu with relative ease, arming the international health community with an arsenal of tests and vaccines to fight back. And a flu virus isn?t particularly complex; it?s just a stretch of RNA transmitted between animals, human and nonhuman, that has evolved to mutate quickly enough to outpace any long-term immunity.

But one stretch of RNA can wreak a lot of havoc. Spanish influenza killed about 50 million people (estimates vary), including 675,000 in the United States, and up to 40 percent of the world?s population was stricken with the flu. Unusually for the flu, the pandemic afflicted the young more than the old. Scientists have since established that the disease triggered an overreaction by the immune system, thus turning a young person?s robust immune system against itself. (Bird flu and swine flu were similarly more deadly in young people.) Victims? lungs overflowed with fluid while their skin, deprived of oxygen, became mottled and discolored. Many sufferers came down with severe nosebleeds?some spewed blood out of their nostrils with such force that nurses had to duck to avoid the flow. Those unable to recover eventually drowned in their own bodily fluids.

Horrifying as the flu was, its reign of terror was mercifully brief: By late 1919, the flu had largely disappeared. Although its survivors and their children faced lifelong health problems, those dark years were largely struck from cultural memory. (Downton Abbey did kill off a character with Spanish influenza, primarily as means to wiggle out of a messy love triangle.)

Scientists, however, never forgot the mysterious pandemic, and research into the 1918 flu experienced something of a renaissance in recent years. In addition to the exhumed Inuit, scientists have studied the organs of flu-suffering soldiers, including a long-forgotten piece of lung tissue stored at a military pathology institute in Washington. Just five years ago, British scientists exhumed the body of Sir Mark Sykes, a British diplomat who was buried in a lead coffin after dying of Spanish influenza in 1919. The scientists had hoped Sykes? special casket might have preserved his body, allowing his organs to be studied and more potential flu RNA to be extracted and sequenced. But the coffin had caved in on the diplomat sometime between 1919 and 2008, and his body tissue was decomposed.

Source: http://feeds.slate.com/click.phdo?i=8bd3d50529ca6f1d70ddf25caf6d29de

freedom riders 9th circuit court of appeals gisele bundchen tom brady randy travis arrested dickens greg kelly cujo

No comments:

Post a Comment